Profiling Go

TOC

Note: I highly recommend also reading this official diagnostics documentation.

Memory Management

Before we dive into the techniques and tools available for profiling Go applications, we should first understand a little bit about its memory model as this can help us to understand what it is we’re seeing in relation to memory consumption.

Go’s implementation is a parallel mark-and-sweep garbage collector. In the traditional mark-and-sweep model, the garbage collector would stop the program from running (i.e. “stop the world”) while it detects unreachable objects and again while it clears them (i.e. deallocates the memory). This is to prevent complications where the running program could end up moving references around during the identification/clean-up phase. This would also cause latency and other issues for users of the program while the GC ran. With Go the GC is executed concurrently, so users don’t notice pauses or delays even though the GC is running.

Types of Profiling

There are a couple of approaches available to us for monitoring performance…

- Timers: useful for benchmarking, as well as comparing before and after fixes.

- Profilers: useful for high-level verification.

Tools Matrix

| Pros | Cons | |

|---|---|---|

| ReadMemStats | - Simple, quick and easy. - Only details memory usage. |

- Requires code change. |

| pprof | - Details CPU and Memory. - Remote analysis possible. - Image generation. |

- Requires code change. - More complicated API. |

| trace | - Helps analyse data over time. - Powerful debugging UI. - Visualise problem area easily. |

- Requires code change. - UI is complex. - Takes time to understand. |

Analysis Steps

Regardless of the tool you use for analysis, a general rule of thumb is to:

- Identify a bottleneck at a high-level

- For example, you might notice a long running function call.

- Reduce the operations

- Look at time spent, or number of calls, and figure out an alternative approach.

- Look at the number of memory allocations, figure out an alternative approach.

- Drill down

- Use a tool that gives you data at a lower-level.

Think about more performant algorithms or data structures.

There may also be simpler solutions.

Take a pragmatic look at your code.

Base Example

Let’s begin with a simple program written using Go 1.9.2…

package main

import (

"log"

)

// bigBytes allocates 100 megabytes

func bigBytes() *[]byte {

s := make([]byte, 100000000)

return &s

}

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

}

Running this program can take ~0.2 seconds to execute.

So this isn’t a slow program, we’re just using it as a base to measure memory consumption.

ReadMemStats

The easiest way to look what our application is doing with regards to memory allocation is by utilising the MemStats from the runtime package.

In the following snippet we modify the main function to print out specific memory statistics.

func main() {

var mem runtime.MemStats

fmt.Println("memory baseline...")

runtime.ReadMemStats(&mem)

log.Println(mem.Alloc)

log.Println(mem.TotalAlloc)

log.Println(mem.HeapAlloc)

log.Println(mem.HeapSys)

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

fmt.Println("memory comparison...")

runtime.ReadMemStats(&mem)

log.Println(mem.Alloc)

log.Println(mem.TotalAlloc)

log.Println(mem.HeapAlloc)

log.Println(mem.HeapSys)

}

If I run this program I’ll see the following output:

memory baseline…

2017/10/29 08:51:56 56480

2017/10/29 08:51:56 56480

2017/10/29 08:51:56 56480

2017/10/29 08:51:56 786432

memory comparison...

2017/10/29 08:51:56 200074312

2017/10/29 08:51:56 1000144520

2017/10/29 08:51:56 200074312

2017/10/29 08:51:56 200704000

So we can see the difference between what the go application was using at the point in time that the main function started and when it finished (after allocating a lot of memory via the bigBytes function). The two items we’re most interested in are TotalAlloc and HeapAlloc.

The total allocations shows us the total amount of memory accumulated (this value doesn’t decrease as memory is freed). Whereas the heap allocations indicate the amount of memory at the point in time when the snapshot was taken, and it can include both reachable and unreachable objects (e.g. objects the garbage collector hasn’t freed yet). So it’s important to realise that the amount of memory ‘in use’ could have dropped after the snapshot was taken.

Take a look at the MemStats docs for more properties (inc. Mallocs or Frees).

Pprof

Pprof is a tool for visualization and analysis of profiling data.

It’s useful for identifying where your application is spending its time (CPU and memory).

You can install it using:

go get github.com/google/pprof

To begin with, let’s understand what a “profile” is:

A Profile is a collection of stack traces showing the call sequences that led to instances of a particular event, such as allocation. Packages can create and maintain their own profiles; the most common use is for tracking resources that must be explicitly closed, such as files or network connections. – pkg/runtime/pprof

Now there are a couple of ways to use this tool:

- Instrument code within binary to generate a

.profilefor analysis during development. - Remotely analyse binary via a web server (no

.profileis explicitly generated).

Note: the profile file doesn’t have to use a

.profileextension (it can be whatever you like)

Generate .profile for analysis during development

In this section we’ll look at profiling both CPU and Memory allocation.

We’ll start with CPU profiling.

CPU Analysis

In the following example we’ve modified the application to import "runtime/pprof" and added the relevant API calls in order to record CPU data:

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

"runtime/pprof"

)

// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

func bigBytes() *[]byte {

s := make([]byte, 100000000)

return &s

}

func main() {

pprof.StartCPUProfile(os.Stdout)

defer pprof.StopCPUProfile()

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

}

Note: we use

os.Stdoutto make the example easier (i.e. no need to create a file) We’ll just use the shell’s ability to redirect output to create the profile file instead.

We can then build and run the application and save the profile data to a file:

go build -o app && time ./app > cpu.profile

Finally we can inspect the data interactively using go tool like so:

go tool pprof cpu.profile

From here you’ll see an interactive prompt has started up.

So let’s execute the top command and see what output we get:

(pprof) top

Showing nodes accounting for 180ms, 100% of 180ms total

flat flat% sum% cum cum%

180ms 100% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.memclrNoHeapPointers /.../src/runtime/memclr_amd64.s

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% main.bigBytes /.../code/go/profiling/main.go (inline)

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% main.main /.../code/go/profiling/main.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.(*mheap).alloc /.../src/runtime/mheap.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.largeAlloc /.../src/runtime/malloc.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.main /.../src/runtime/proc.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.makeslice /.../src/runtime/slice.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.mallocgc /.../src/runtime/malloc.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.mallocgc.func1 /.../src/runtime/malloc.go

0 0% 100% 180ms 100% runtime.systemstack /.../src/runtime/asm_amd64.s

So this suggests the biggest CPU consumer is runtime.memclrNoHeapPointers.

Let’s now view a “line by line” breakdown to see if we can pinpoint the CPU usage further.

We’ll do this by using the list <function regex> command.

We can see from the top command that our main function is available via main.main.

So let’s list any functions within the main namespace:

(pprof) list main\.

Total: 180ms

ROUTINE ======================== main.bigBytes in /.../go/profiling/main.go

0 180ms (flat, cum) 100% of Total

. . 6: "runtime/pprof"

. . 7:)

. . 8:

. . 9:// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

. . 10:func bigBytes() *[]byte {

. 180ms 11: s := make([]byte, 100000000)

. . 12: return &s

. . 13:}

. . 14:

. . 15:func main() {

. . 16: pprof.StartCPUProfile(os.Stdout)

ROUTINE ======================== main.main in /.../code/go/profiling/main.go

0 180ms (flat, cum) 100% of Total

. . 15:func main() {

. . 16: pprof.StartCPUProfile(os.Stdout)

. . 17: defer pprof.StopCPUProfile()

. . 18:

. . 19: for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

. 180ms 20: s := bigBytes()

. . 21: if s == nil {

. . 22: log.Println("oh noes")

. . 23: }

. . 24: }

. . 25:}

OK, so yes we can see that 180ms is spent in the bigBytes function and pretty much all of that function’s time is spent allocating memory via make([]byte, 100000000).

Memory Analysis

Before we move on, let’s look at how to profile our memory consumption.

To do this we’ll change our application slightly so that StartCPUProfile becomes WriteHeapProfile (we’ll also move this call to the bottom of our main function otherwise if we keep it at the top of the function no memory has been allocated at that point). We’ll also remove the StopCPUProfile call altogether (as recording the heap is done as a snapshot rather than an ongoing process like with the CPU profiling):

package main

import (

"log"

"os"

"runtime/pprof"

)

// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

func bigBytes() *[]byte {

s := make([]byte, 100000000)

return &s

}

func main() {

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

pprof.WriteHeapProfile(os.Stdout)

}

Again, we’ll build and execute the application and redirect the stdout to a file (for simplicity), but you could have created the file dynamically within your application if you so choose:

go build -o app && time ./app > memory.profile

At this point we can now run pprof to interactively inspect the memory profile data:

go tool pprof memory.profile

Let’s run the top command and see what the output is:

(pprof) top

Showing nodes accounting for 95.38MB, 100% of 95.38MB total

flat flat% sum% cum cum%

95.38MB 100% 100% 95.38MB 100% main.bigBytes /...ain.go (inline)

0 0% 100% 95.38MB 100% main.main /.../profiling/main.go

0 0% 100% 95.38MB 100% runtime.main /.../runtime/proc.go

For a simple example application like we’re using, this is fine as it indicates pretty clearly which function is responsible for the majority of the memory allocation (main.bigBytes).

But if I wanted a more specific breakdown of the data I would execute list main.:

(pprof) list main.

Total: 95.38MB

ROUTINE ======================== main.bigBytes in /.../go/profiling/main.go

95.38MB 95.38MB (flat, cum) 100% of Total

. . 6: "runtime/pprof"

. . 7:)

. . 8:

. . 9:// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

. . 10:func bigBytes() *[]byte {

95.38MB 95.38MB 11: s := make([]byte, 100000000)

. . 12: return &s

. . 13:}

. . 14:

. . 15:func main() {

. . 16: for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

ROUTINE ======================== main.main in /.../code/go/profiling/main.go

0 95.38MB (flat, cum) 100% of Total

. . 12: return &s

. . 13:}

. . 14:

. . 15:func main() {

. . 16: for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

. 95.38MB 17: s := bigBytes()

. . 18: if s == nil {

. . 19: log.Println("oh noes")

. . 20: }

. . 21: }

. . 22:

This indicates where all our memory is allocated on a “line-by-line” basis.

Remotely analyse via web server

In the following example we’ve modified the application to start up a web server and we’ve imported the "net/http/pprof" package which automatically profiles what’s happening.

Note: if your application already uses a web server, then you don’t need to start another. The pprof package will hook into your web server’s multiplexer.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"log"

"net/http"

_ "net/http/pprof"

"sync"

)

// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

func bigBytes() *[]byte {

s := make([]byte, 100000000)

return &s

}

func main() {

var wg sync.WaitGroup

go func() {

log.Println(http.ListenAndServe("localhost:6060", nil))

}()

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

wg.Add(1)

wg.Wait() // this is for the benefit of the pprof server analysis

}

When you build and run this binary, first visit the web server the code is running.

You’ll find that the pprof data is accessible via the path /debug/pprof/:

http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/

You should see something like:

profiles:

0 block

4 goroutine

5 heap

0 mutex

7 threadcreate

full goroutine stack dump

/debug/pprof/

Where block, goroutine, heap, mutex and threadcreate are all links off to the recorded data; and by ‘recorded data’ I mean they each link through to a different .profile. This isn’t particularly useful though. A tool is needed to process these .profile data files.

We’ll come back to that in a moment, first let’s understand what these five profiles represent:

- block: stack traces that led to blocking on synchronization primitives

- goroutine: stack traces of all current goroutines

- heap: a sampling of all heap allocations

- mutex: stack traces of holders of contended mutexes

- threadcreate: stack traces that led to the creation of new OS threads

The web server can also generate a 30 second CPU profile, which you can access via http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/profile (it won’t be viewable in the browser, instead it’ll be downloaded to your file system).

The CPU profile endpoint is not listed when viewing /debug/pprof/ simply because the CPU profile has a special API, the StartCPUProfile and StopCPUProfile functions that stream output to a writer during profiling, hence this hidden endpoint will ultimately download the results to your file system (we looked at how to use this API in the previous section).

The web server can also generate a “trace” file, which you can access via http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/trace?seconds=5 (again, it’s not listed for similar reasons as the CPU profile - in that it generates file output that is downloaded to your file system). This trace file out requires the use of go tool trace (which we’ll cover in the next section).

Note: more info on pprof options can be found here: golang.org/pkg/net/http/pprof/

If you’re using a custom URL router, you’ll need to register the individual pprof endpoints:

package main

import (

"net/http"

"net/http/pprof"

)

func message(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

w.Write([]byte("Hello World"))

}

func main() {

r := http.NewServeMux()

r.HandleFunc("/", message)

r.HandleFunc("/debug/pprof/", pprof.Index)

r.HandleFunc("/debug/pprof/cmdline", pprof.Cmdline)

r.HandleFunc("/debug/pprof/profile", pprof.Profile)

r.HandleFunc("/debug/pprof/symbol", pprof.Symbol)

r.HandleFunc("/debug/pprof/trace", pprof.Trace)

http.ListenAndServe(":8080", r)

}

So ideally you would use go tool pprof on the command line.

As this allows you to more easily interpret and interrogate the data interactively.

To do this, you have to run your binary as before and then, in a separate shell, execute:

go tool pprof http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/<.profile>

For example, let’s look at the memory heap profile data:

go tool pprof http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap

From here you’ll see an interactive prompt has started up:

Fetching profile over HTTP from http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap

Saved profile in /.../pprof.alloc_objects.alloc_space.inuse_objects.inuse_space.005.pb.gz

Type: inuse_space

Time: Oct 27, 2017 at 10:01am (BST)

Entering interactive mode (type "help" for commands, "o" for options)

(pprof)

Note: you’ll see the “type” is set to

inuse_space(meaning how much memory is still in use)

As shown, you can type either help or o to see what’s available to use.

Here are a couple of useful commands:

top: outputs top entries in text formtopK: where K is a number (e.g. top2 would show top two entries)list <function regex>: outputs top entries in text form

For example, if I execute top then we’d see the following output:

Showing nodes accounting for 95.38MB, 100% of 95.38MB total

flat flat% sum% cum cum%

95.38MB 100% 100% 95.38MB 100% main.bigBytes /...ain.go (inline)

0 0% 100% 95.38MB 100% main.main /.../profiling/main.go

0 0% 100% 95.38MB 100% runtime.main /.../runtime/proc.go

For a simple example application like we’re using, this is fine as it indicates pretty clearly which function is responsible for the majority of the memory allocation (main.bigBytes).

But if I wanted a more specific breakdown of the data I would execute list main.main:

Total: 95.38MB

ROUTINE ======================== main.main in /.../profiling/main.go

95.38MB 95.38MB (flat, cum) 100% of Total

. . 8: "sync"

. . 9:)

. . 10:

. . 11:// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

. . 12:func bigBytes() *[]byte {

95.38MB 95.38MB 13: s := make([]byte, 100000000)

. . 14: return &s

. . 15:}

. . 16:

. . 17:func main() {

. . 18: fmt.Println("starting...")

This indicates where all our memory is allocated on a “line-by-line” basis.

I noted earlier that the default “type” for the heap analysis was “memory still in use”. But there is an alternative type which indicates the amount of memory that was allocated in total throughout the lifetime of the program. You can switch to that mode using the -alloc_space flag like so:

go tool pprof -alloc_space http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap

Let’s see the difference in the output by executing the list command:

(pprof) list main.bigBytes

Total: 954.63MB

ROUTINE ======================== main.bigBytes in /.../go/profiling/main.go

953.75MB 953.75MB (flat, cum) 99.91% of Total

. . 7: "sync"

. . 8:)

. . 9:

. . 10:// bigBytes allocates 10 sets of 100 megabytes

. . 11:func bigBytes() *[]byte {

953.75MB 953.75MB 12: s := make([]byte, 100000000)

. . 13: return &s

. . 14:}

. . 15:

. . 16:func main() {

. . 17: var wg sync.WaitGroup

Note: if you wanted to be explicit you could have used the “in use” type like so:

go tool pprof -inuse_space http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap

The reason to choose either -inuse_space or -alloc_space will depend on where your specific concerns are focused. For example, if you’re concerned about garbage collection performance then you’ll want to look at the “allocated” memory (i.e. -alloc_space).

Note: you can also inspect the number of objects (not just their space) with

-inuse_objectsand-alloc_objects.

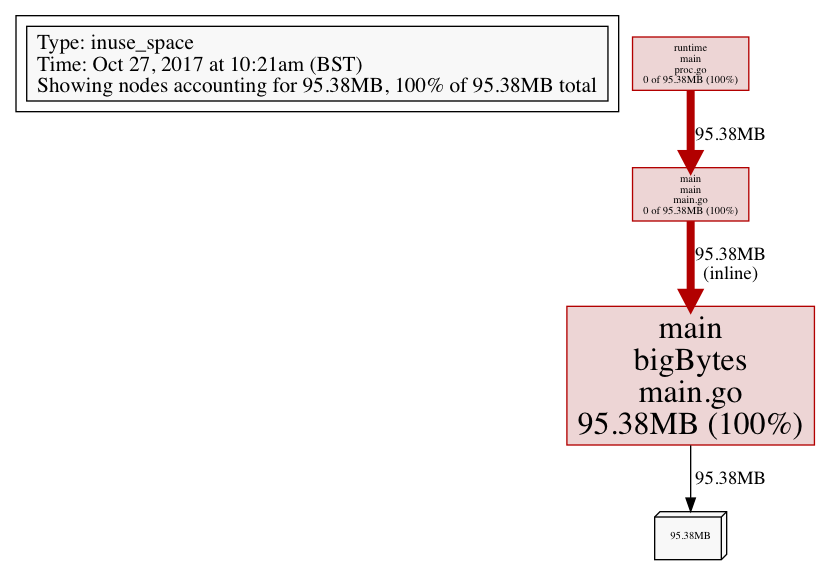

Image Generation

You can also generate an image of your analysis data using either the flag -png, -gif or -svg and then redirecting stdout to a filename like so:

go tool pprof -png http://localhost:6060/debug/pprof/heap > data.png

This generates an image that looks like the following (notice how the bigger the box, the more resources it’s consuming - this helps you ‘at a glance’ to identify a potential problem zone):

Note: you can also output as a PDF with

Web UI

Finally, there is a interactive web ui coming for pprof in the near future (as of November 2017).

See this post for more details.

But in short you can get the updated pprof tool from GitHub and then execute it with the new flag -http (e.g. -http=:8080).

Trace

Trace is a tool for visualization and analysis of trace data.

It’s suited at finding out what your program is doing over time, not in aggregate.

Note: if you want to track down slow functions, or generally find where your program is spending most of its CPU time, then you should consider using

go tool pprofinstead.

Let’s first modify our application to utilise tracing…

func main() {

trace.Start(os.Stdout)

defer trace.Stop()

for i := 0; i < 10; i++ {

s := bigBytes()

if s == nil {

log.Println("oh noes")

}

}

var wg sync.WaitGroup

wg.Add(1)

var result []byte

go func() {

result = make([]byte, 500000000)

log.Println("done here")

wg.Done()

}()

wg.Wait()

log.Printf("%T", result)

}

So, as far as utilising tracing, all we’ve done is import "runtime/trace" and then added calls to the trace.Start and trace.Stop functions (we defer the trace.Stop in order to ensure we trace everything our application is doing).

Additionally we create a goroutine and allocate a large 500mb slice of bytes. We wait for the goroutine to complete and then we log the type of the result. We’re doing this just so we have some additional spike data to visualise.

Now let’s re-compile our application, generate the trace data and open it with the trace tool…

$ go build -o app

$ time ./app > app.trace

$ go tool trace app.trace

Note: you can also generate a pprof compatible file from a trace by using the

-pprofflag (if you decided you wanted to dynamically inspect the data that way). See the go documentation for more details.

Here’s the output from running go tool trace app.trace:

2017/10/29 09:30:40 Parsing trace...

2017/10/29 09:30:40 Serializing trace...

2017/10/29 09:30:40 Splitting trace...

2017/10/29 09:30:40 Opening browser

You’ll now see your default web browser should have automatically opened to:

http://127.0.0.1:60331

Note: it’s best to use Chrome, as

go tool traceis designed to work best with it.

The page that is loaded will show the following list of links:

- View trace

- Goroutine analysis

- Network blocking profile

- Synchronization blocking profile

- Syscall blocking profile

- Scheduler latency profile

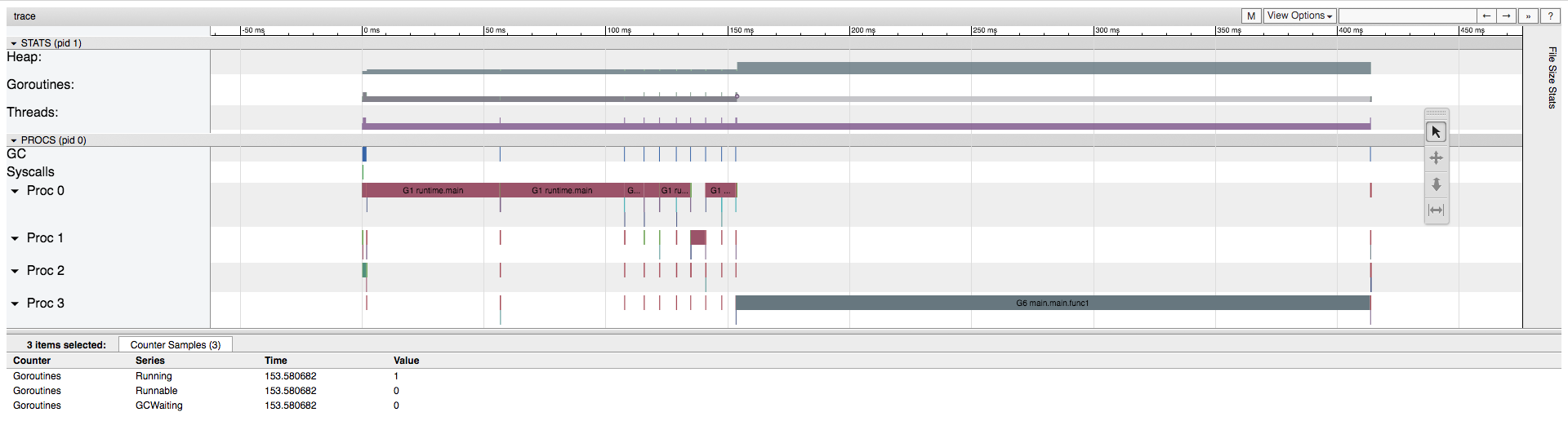

Each of these items can give a good insight as to what your application is doing, but we’re most interested in the first one “view trace”. Click it and it’ll give you a complete overview of what your application is doing in an interactive graph.

Note: press

<Shift-?>to show shortcut keys, likewandsfor zooming in/out.

Goroutines

If you zoom in enough on the graph you’ll see the “goroutines” segment is made up of two colours: a light green (runnable goroutines) and a dark green (running goroutines). If you click on that part of the graph you’ll see the details of that sample in the bottom preview of the screen. It’s interesting to see how, at any given moment, there can be multiple goroutines but not all of them are necessarily running all at once.

So in our example you see the program moves between having one goroutine ready to run, but not actually running (e.g. it’s “runnable”) and then we move towards two goroutines running (e.g. they’re both “running” and so there are no goroutines left marked as “runnable”).

It’s also interesting to see the correlation between the number of goroutines running and the number of actual underlying OS threads being utilised (i.e. the number of threads the goroutines are being scheduled on to).

Threads

Again, if you zoom in enough on the graph you’ll see the “threads” segment is made up of two colours: a light purple (syscalls) and a dark purple (running threads).

What’s interesting about the “heap” segment of the UI is that we can see for a short while we never allocate more (total) than 100mb to the heap because the go garbage collection is running concurrently (we can see it running on various processes/threads) and is clearing up after us.

This makes sense because in our code we allocate 100mb of memory and then assign it to a variable s which is scoped to exist only within the for loop block. Once that loop iteration ends the s value isn’t referenced anywhere else so the GC knows it can clean up that memory.

Heap

We can see as the program moves on that we eventually start seeing some contention and so the total allocated heap becomes 200mb then back and forth between 100mb and 200mb (this is because the GC isn’t running all the time). Then near the end we see the 500mb spike that I added to our code as the total allocated amount of memory in the heap shoots to 600mb.

But at that point, if we click on the spike in heap allocation, we can see in the bottom preview window the “NextGC” run indicates that the total allocated should be zero (which makes sense as that’s the end of the program).

Procs

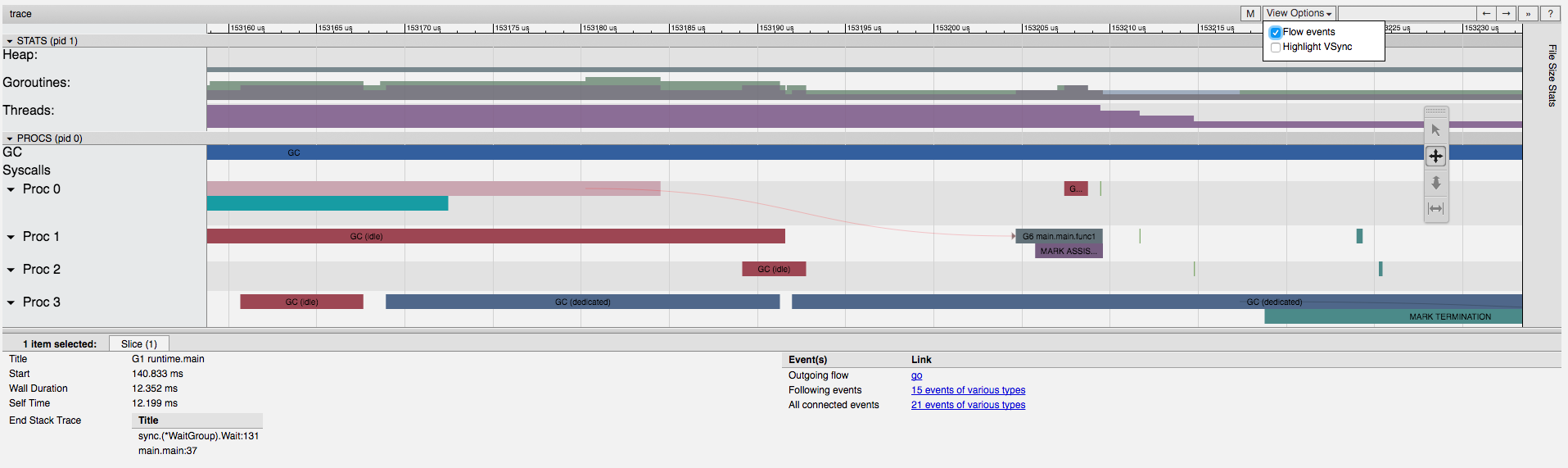

In the “procs” section of the UI we can see during our large 500mb allocation that Proc 3 has a new goroutine running main.main.func1 (which is our go function that’s doing the allocating).

If you were to “View Options” and then tick “Flow events” you’ll see an arrow from the main.main function going towards the main.main.func1 function running on a separate process/thread (probably a bit difficult to see in the below image, but it’s definitely there).

So it’s good to be able to visually see the correlation between first of all the main.main.func1 goroutine running and the memory allocation occurring at that time, but also being able to see the cause and effect (i.e. the flow) of the program (i.e. knowing what exactly triggered the new goroutine to be spun up).

Conclusion

That’s our tour of various tools for profiling your Go code. Take a look at my earlier article on profiling Python for more of the same.