Bits and Bytes

TOC

Introduction

So this is a bit of a random journey through some different computer based subjects. Things that I felt I should try to better understand. Some of it will be very basic, but hopefully it’ll be useful to those who are new to tech, and are interested in learning these things (or old dogs like me who should know better).

Bit

The word bit is short for binary digit.

A bit is either a 1 (true) or a 0 (false).

Computers only understand the binary format (i.e. base-2)

We discuss ‘base’ numbers below

Byte

A grouping of eight bits is called a byte.

Read the next section to realise why I mention this tidbit of information

RAM

The word ram is an acronym for random access memory.

It’s non-persistent memory.

Meaning it is lost when your machine is restarted, and persists only for the lifetime of the program using it.

RAM consists of bits, but each segment of memory is actually a grouping of eight bits (which we already know is called a byte).

So in short we would say RAM is made up of bytes.

Bytes are uniquely numbered to allow easy lookup of their contents.

A byte’s unique number is also referred to as its address.

Bit and RAM Visualisation

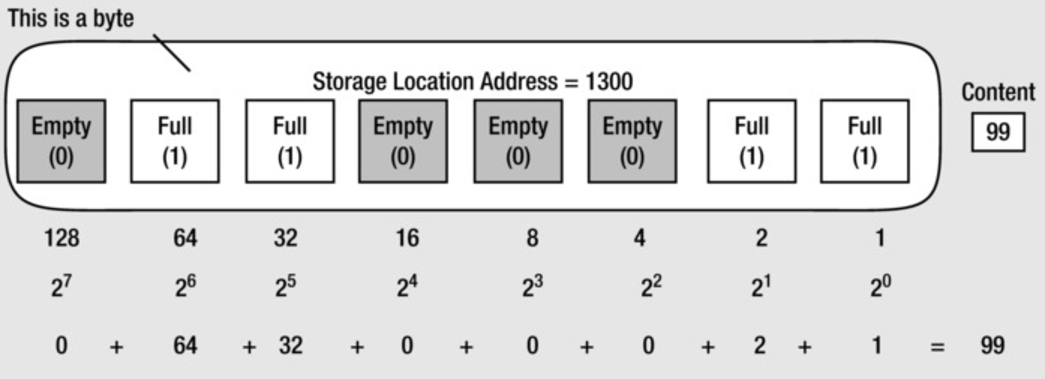

We can see that each bit has an associated value which is calculated using the power of base-2 (we’ll cover base numbers shortly).

So:

- 20 = 1

- 21 = 2

- 22 = 4 (i.e.

2 * 2) - 23 = 8 (i.e.

2 * 2 * 2) - 24 = 16 (i.e.

2 * 2 * 2 * 2) - 25 = 32 (i.e.

2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2) - 26 = 64 (i.e.

2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2) - 27 = 128 (i.e.

2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2 * 2)

With this information we can identify the value assigned by adding up the numbers associated with the ones and zeros.

So in the image we can see four of the bits are given 1 (on) and the rest are 0 (off), meaning if we add up all the associated values of the bits that are ‘on’ we get 99 (e.g. 64 + 32 + 2 + 1).

Basic Bit Operators

You may have seen bit operators like << or >> and wondered what they mean (generally referred to as ‘bitwise operators’). Essentially they manipulate bits.

Here are some examples:

64 >> 1 = 32

1 << 3 = 8

1 << 7 = 128

1 << 15 = 32768

So if we keep in mind the earlier image of our 8 bits in a byte memory representation, and that each bit had its own value (as described above), we can see (for example) that if we started at 64 and moved to the right by 1 bit, the next bit would be the one assigned the value 32. Hence, 64 >> 1 results in the value 32.

Similarly, if we start with the bit value 1 and move to the left by 15 bits we’ll get back the result of 32768 because although we’ve only shown eight bit spaces above, you can just keep moving to the left (64 * 2 = 128, 128 * 2 = 256, now keep going seven more places until you reach the fifteenth bit… 256 * 2 = 512, 512 * 2 = 1024, 1024 * 2 = 2048, 2048 * 2 = 4096, 4096 * 2 = 8192, 8192 * 2 = 16384, 16384 * 2 = 32768).

For more bitwise operators, refer to these posts: https://wiki.python.org/moin/BitwiseOperators and https://medium.com/learning-the-go-programming-language/bit-hacking-with-go-e0acee258827

Bits and ASCII

ASCII is a set of codes where each ‘code point’ represents a textual character such as a 1, a, z, !, ? etc.

Each code point has an associated binary number. For example, a has the binary number 0110 0001 which if we add up the values associated with those specific bits we’ll find it’ll yield the code point number 97. In ASCII the character a is code point 97.

Bits and Numbers

1 kilobyte (or 1KB) is 1,024 bytes.

1,024 bytes is 8192 bits (8192/8 or 8*1024, whichever you prefer)

The following explanation is taken from “Beginning C” by Apress Publishing…

You might be wondering why we don’t work with simpler, more rounded numbers, such as a thousand, or a million, or a billion. The reason is this: there are 1,024 numbers from 0 to 1,023, and 1,023 happens to be 10 bits that are all 1 in binary: 11 1111 1111, which is a very convenient binary value. So while 1,000 is a very convenient decimal value, it’s actually rather inconvenient in a binary machine—it’s 11 1110 1000, which is not exactly neat and tidy. The kilobyte (1,024 bytes) is therefore defined in a manner that’s convenient for your computer, rather than for you.

So if we add up 512+256+128+64+32+16+8+4+2+1 (notice this takes the existing 8 bit calculation from the above image and continues it for another two bits) we get 1023.

IPs

Here is an example IPv4 IP:

216.27.61.137

IPv4 IPs are expressed in decimal format.

Note: IPv6 IPs are eight 4-character hexadecimal numbers,

which represent 16 bits each (for a total of 128 bits)

e.g.2001:0db8:0a0b:12f0:0000:0000:0000:0001

To translate the above IP into binary form (for the sake of a computer to process it), we could use the above visualisation image to help us. The end result of which would look like this:

11011000.00011011.00111101.10001001

Which breaks down into:

11011000: 128 + 64 + 16 + 8 = 21600011011: 16 + 8 + 2 + 1 = 2700111101: 32 + 16 + 8 + 4 + 1 = 6110001001: 128 + 8 + 1 = 137

This explains why each of the four numbers within the decimal formatted version (i.e. 216.27.61.137) are called octets, as they represent eight bits (or a ‘byte’ as we learned earlier) when viewed in binary form.

This also explains why IPv4 IPs are considered 32-bit numbers, because if you add each of the bits together (i.e. the number of total bits, not the value assigned to each bit) you’ll find there are a total of 32 bits that make up the IP.

Each bit can have two different states (1 or zero), meaning the total number of potential combinations per octet can be either 28 or 256. Meaning each octet can contain a potential value between zero and 255. Meaning if we were to combine the four octets, we could potentially have 4,294,967,296 variations.

We can see the decimal represenation of an IPv4 IP is made up of four base-10 numbers (216, 27, 61, 137). Where each of those four numbers represent the binary equivalent (216=11011000, 27=00011011, 61=00111101, 137=10001001), which is a base-2 representation of a byte (or octet).

If you’re unsure of what base numbers are and how they work, then read on…

Base Numbers

It’s worth quickly covering what base numbers are as they help us understand the other different protocols we use on a regular basis, such as binary and things like IPs.

Any number can be represented in multiple ways using a different base numbering system.

There are many numbering systems, but the typical ones we’re used to are:

- Base 10 (Decimal)

- Base 2 (Binary)

- Base 8 (Octal)

- Base 16 (Hexadecimal)

The standard number system we (as humans) are most familiar with is called base-10 and it consists of the following numbers:

0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9

Notice there are ten numbers, hence it is called the base-10 system

If we were to look at a number like 66, then this would tell us the number is made up of 6 tens and six units.

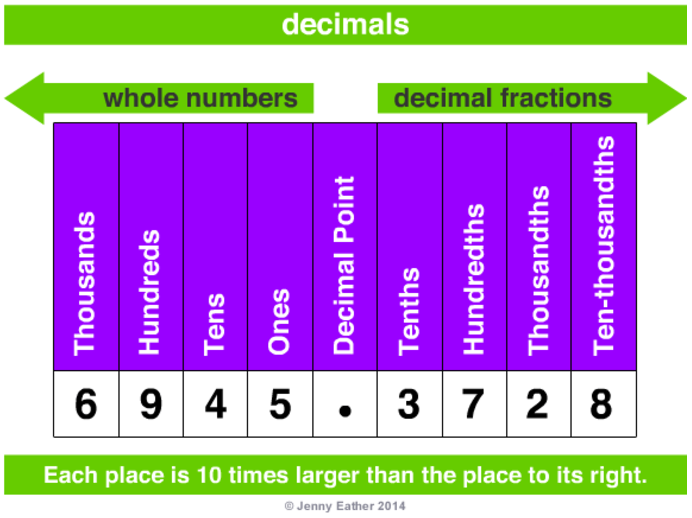

These numbers (0-9) represent ‘whole numbers’, while in the base-10 system we can also use a decimal point to represent decimal fractions of a number (e.g. 1.2).

Below is an image, credit to Jenny Eather, that helps us visualise this model:

The ‘base number’ is the number of numbers within the system. So base-10 has 10 numbers (0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9) whereas binary is base-2 because it uses two numbers only (0, 1).

If you want to know the unit each number in a system represents (we’ll use base-10 as the example, thanks to the following visualisation credited to Jenny Eather), then you calculate this using the power of the base number.

So, as per the above visualisation, we can see:

- 103:

10*10*10: 1000 (thousands) - 102:

10*10: 100 (hundreds) - 101:

10: 10 (tens) - 100:

1: 1 (unit)

So in practical terms, if you have a number like 75 and want to represent it as base-10:

- 5 (100: 5 units)

- 7 (101: 7 tens)

Similarly, if we had a number like 675 and want to represent it as base-10:

- 5 (100: 5 units)

- 7 (101: 7 tens)

- 6 (102: 6 hundreds)

You can indicate what base you wish to represent a number like so:

nb

Where n is the number and b is the base you wish to state it is in.

For example:

7510

This is the number 75 and we’re stating the base it represents is 10.

This is useful when you’ve converted a number like 75 into a different base (let’s say base-8, which would be 113) and you want to give that number in the proper context to someone else. You could write it as 1138.

Convert Base-10 into Base-2⁄8

Note: the steps are the same for converting to base-2 and base-8

Now let’s consider how to convert the number 75 into another base, like base-8. To do so, follow these steps

- divide the number (75) by the desired base (8) (take note of the remainder: 3)

- take the result (9) and do the same (i.e. divide by the base and take note of the remainder)

- keep doing this until the result of dividing the previous answer by the base is zero

- now write out the remainders bottom to top, and that’s the number in base-8

In long form this looks like this:

- 75 (number) / 8 (base) = 9 (rounded) with a remainder of 3

- 9 (previous answer) / 8 (base) = 1 (rounded) with a remainder of 1

- 1 (previous answer) / 8 (base) = 0 (rounded) with a remainder of 1

Meaning 75 evaluated in base-8 would be 113 (all the remainders concatenated together, ‘bottom up’)

Convert Base-10 into Base-16

The algorithm for converting from base-10 into base-2 and base-8 works basically the same for converting into base-16. But there is one caveat whereby a remainder can be in the double digits, and apparently (for reasons I don’t completely understand) we don’t want that, and so the number system was designed to replace the six instances where this can occur (the remainders being: 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15) with a alpha-numeric equivalent:

- 10-A

- 11-B

- 12-C

- 13-D

- 14-E

- 15-F

So if we want to convert 11010 into a hexadecimal, the outcome of the algorithm would be:

- 110 (number) / 16 (base) = 6 (rounded) with a remainder of 14

- 6 (previous answer) / 16 (base) = 0 (rounded) with a remainder of 6

We know that we need to replace 14 (a double digit remainder) with the letter E (see above mapping).

Meaning 110 evaluated in base-16 would be 6E

Let’s try it again, but with the number 41110:

- 411 (number) / 16 (base) = 25 (rounded) with a remainder of 11

- 25 (previous answer) / 16 (base) = 1 (rounded) with a remainder of 9

- 1 (previous answer) / 16 (base) = 0 (rounded) with a remainder of 1

We know that we need to replace 11 with the letter B.

Meaning 411 evaluated in base-16 would be 19B

Convert Any Base to Base-10

What if you want to convert a base-8 number (let’s say 113, why not) into base-10? The algorithm is to multiple the individual numbers by their associated power of the base and then add the numbers together.

So here are the base-8 powers:

- 3: 80

- 1: 81

- 1: 82

And here is the algorithm:

- 3 x 80 = 3

- 1 x 81 = 8 (i.e.

1*8) - 1 x 82 = 64 (i.e.

1*(8 * 8)) - 3 + 8 + 64 = 75

If you’re dealing with base-16, then again it’s the same but the difference is you’re translating the letter back into the corresponding number.

Let’s convert 19B from base-16 back into base-10:

- B x 160 (11 x 160) = 11

- 9 x 161 = 144

- 1 x 162 = 256

- 11 + 144 + 256 = 411

Let’s try one more conversion between base-16 to base-10. The number is 1A4:

- 4 x 160 = 4

- A x 161 (10 x 161) = 160

- 1 x 162 = 256

- 4 + 160 + 256 = 420

CIDR

A CIDR is a range of IP addresses. We can use our understanding of bits, bytes and octets to understand the format of a CIDR.

A CIDR typically resembles something like:

10.0.0.0/n

Where n is given the value 8, 16, 24, or 32 and these represent each of the 8-bit blocks that make up the IP.

If we want an IP range between 10.0.0.0 and 10.255.255.255, we’d specify the CIDR as 10.0.0.0/8.

What 8 states is that the last 8 bits of the 32-bit number is accounted for (this being the 10 we’ve specified in our example). Meaning the rest of the 8-bit segments can be added up to their max of 255 (meaning the last IP in this CIDR range would be 10.255.255.255).

Similarly if we want an IP range between 10.0.0.0 and 10.0.255.255, we’d specify the CIDR as 10.0.0.0/16.

Again, 16 states that the next 8-bits segment of the 32-bit number is now accounted for (this being the 0 we’ve specified in our example 10.0). Meaning the rest of the 8-bit segments can be added up to their max of 255 (meaning the last IP in this CIDR range would be 10.0.255.255).

And so on…

So 10.0.0.0/24 gives us an ip range of 10.0.0.0 to 10.0.0.255 (256 IPs).

Whereas 10.0.0.0/32 gives us an ip range of 1 ip (10.0.0.0 to 10.0.0.0).

Note: you can use a tool such as http://www.ipaddressguide.com/cidr to help you generate CIDRs

We can use the earlier byte visualisation table matrix to help us manually calculate a CIDR range.

I’ve reproduced it below with a HTML table:

Note: you’ll likely need to scroll to the right to see the start of the 32-bit

| IP | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 Bit Blocks | 8 bits [24-31] | 8 bits [16-23] | 8 bits [08-15] | 8 bits [00-07] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 Bit # | 31 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 25 | 24 | 23 | 22 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 16 | 15 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 09 | 08 | 07 | 06 | 05 | 04 | 03 | 02 | 01 | 00 |

| Decimal | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Binary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Conclusion

There you go. A whirlwind ride through different basic computer tech topics. As always, if I’ve gotten anything wrong then just let me know on twitter.